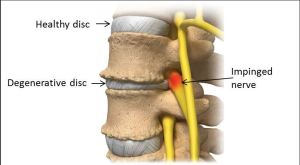

During adulthood, the soft center of an intervertebral disk (nucleus pulposus) binds less water, and the outer ring (annulus fibrosus) undergoes minor tearing as the disk dehydrates/shrinks. This is disk degeneration or degenerative disk disease (DDD). If the disks shrink too much, spinal ligaments may loosen, rendering the spine less stable, and possibly more injury prone. Healthy disks lack pain receptors. Degenerated disks do possess pain-sensing nerves (nocioceptors), so DDD may be painful. DDD (and DISH) may present as low back pain (with or without buttock pain) that may be worse with activity, and occasional night pain. Laying usually improves the pain. Parts of spine may be a little tender to the touch, and there is usually no pain down the legs. If the disks shrink so much that the veretrbae come close together, either arthritis or sciatica may occur. However, in large studies, MRI visualized disk herniation does not correlate well with pain, and studies suggest there is no direct link between DDD (as well as degenerative arthritis) and low back pain. [16,19-23]

DISH syndrome is a type of arthritis in which degenerated disks fuse with arthritic (extra growth) vertebral bones. Extra bone growths, called osteophytes (like you see with bunions) form after long term wear and tear to vertebral bone. “Bridging osteophytes”, bone/disk complexes grow together as damaged disks start to “ossify” – become like bone. These fusions of vertebrae and disks/confluent osteophytes create spinal rigidity of the involved vertebrae, making the affected portion of the spine unable to move well. This condition mainly affects men over 60 years of age. As a more chronic and indolent condition, the back pain tends to be mild, and includes morning and evening spinal stiffness as well as regions of decreased spinal motion. X-ray findings may demonstrate loss of disk height/space, osteophytes, and/or a “vacuum sign”. An advanced complication occurs when the vertebrae above and below the fused area get overused, and can become damaged and unstable from the wear and tear at those sites. Treatments include physical therapy, walking, non-steroidal antiinflammatory medication and pain management with non-narcotics, narcotics, and sometimes anti-depressants.

X

1 Anderssen GBJ. Frymoyer JW (ed.). The epidemiology of spinal disorders, in The Adult Spine: Principles and Practice. New York: Raven Press; 1997:93-141.

2 Cunningham LS, Kelsey JL. Epidemiology of musculoskeletal impairments and associated disability. Am J Public Health. Jun 1984;74(6):574-9. [Medline].

3 National Center for Health Statistics (1977):. Limitations of activity due to chronic conditions, United States. Series 10, No.111. 1974..

4 National Center for Health Statistics (1975):. Physician visits, volume and interval since last visit, United States. 1971. Series 10, No.97.

5 Nachemson Al, Waddell G, Norland AL. Nachemson AL, Jonsson E (eds.). Epidemiology of Neck and Low Back Pain, in. Neck and Back Pain: The scientific evidence of causes, diagnoses, and treatment. Philadelphia: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins; 2000:165-187.

6 Mayer TG, Gatchel RJ. Functional restoration for spinal disorders: The sports medicine approach. Philadelphia: Lea & Febiger; 1988.

7 Biering-Sorenson F. Low back trouble and a general population of 30-, 40-, 50-, and 60–year-old men and women. Dan Med Bull. 1982;29:289-99.

8 Damkot DK, Pope MH, Lord J, Frymoyer JW. The relationship between work history, work environment and low-back pain in men. Spine (Phila Pa 1976). May-Jun 1984;9(4):395-9. [Medline].

9 “Acupuncture Energetics: A Clinical Approach for Physicians”. Joseph M. Helms. Medical Acupuncture Publishers; 1st Edition. (1995)

10 “Foundations of Chinese Medicine: A Comprehensive Text for Acupuncturists and Herbalists”. Giovanni Maciocia. Churchill Livingstone; 2 Edition (July, 2005).

11 “Travell & Simons’ Myofascial Pain and Dysfunction: The Trigger Point Manual”. David G. Simons, Janet G. Travell, Lois S. Simons, Barbara D. Cummings. Lippincott Williams & Wilkins; 2 edition (1998)

12 “Traditional Chinese Medicine Cupping Therapy”. Ilkay Chirali. Churchill & Livinstone; 2 editioin (2007)

13 Argoff CE, Wheeler AH. Backonja MM, ed. Spinal and radicular pain syndromes. Philadelphia, WB Saunders: Neurologic Clinics; 1998:833-45.

14 Wheeler AH. Diagnosis and management of low back pain and sciatica. Am Fam Physician. Oct 1995;52(5):1333-41, 1347-8.

15 Wheeler AH, Murrey DB. Spinal pain: pathogenesis, evolutionary mechanisms, and management, in Pappagallo M (ed). The neurological basis of pain. New York: McGraw-Hill; 2005:421-52.

16 “Essentials of Musk Care”

17 Mooney V. Presidential address. International Society for the Study of the Lumbar Spine. Dallas, 1986. Where is the pain coming from?. Spine (Phila Pa 1976). Oct 1987;12(8):754-9. .

18 Waddell G. 1987 Volvo award in clinical sciences. A new clinical model for the treatment of low-back pain. Spine (Phila Pa 1976). Sep 1987;12(7):632-44.

19 Frymoyer JW. Back pain and sciatica. N Engl J Med. Feb 4 1988;318(5):291-300.

20 Argoff CE, Wheeler AH. Backonja MM, ed. Spinal and radicular pain syndromes. Philadelphia, WB Saunders: Neurologic Clinics; 1998:833-45.

21 Mooney V. Presidential address. International Society for the Study of the Lumbar Spine. Dallas, 1986. Where is the pain coming from?. Spine (Phila Pa 1976). Oct 1987;12(8):754-9.

22 Wheeler AH, Hanley EN Jr. Nonoperative treatment for low back pain. Rest to restoration. Spine (Phila Pa 1976). Feb 1 1995;20(3):375-8. [Medline].

23 Jensen MC, Brant-Zawadzki MN, Obuchowski N, Modic MT, Malkasian D, Ross JS. Magnetic resonance imaging of the lumbar spine in people without back pain. N Engl J Med. Jul 14 1994;331(2):69-73